View News

Introduction: The Aravalli Range and Its Constitutional Significance

Introduction: The Aravalli Range and Its Constitutional Significance

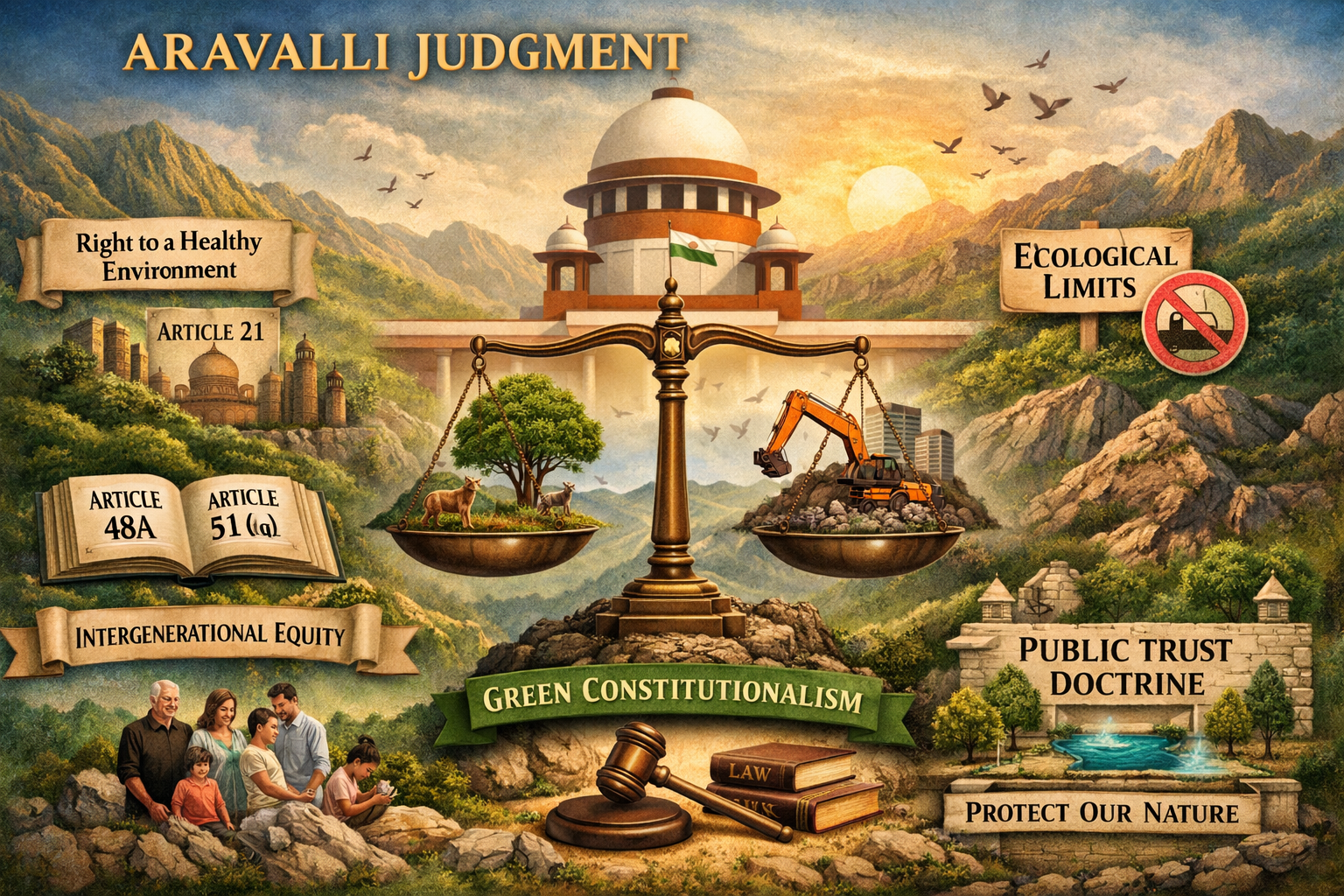

One of the oldest mountain systems in the world, the Aravalli range occupies a unique ecological and constitutional position in India’s environmental landscape. Stretching across several states in northern and western India, the range plays a critical role in preventing desertification, regulating regional climate, recharging groundwater aquifers, and sustaining biodiversity. Over the decades, however, rampant mining, unauthorized construction, and unplanned urban expansion have severely degraded this fragile ecosystem. Against this backdrop, the recent judicial intervention to protect the Aravalli region assumes profound importance.

The Aravalli judgment is not merely a ruling addressing environmental violations in a specific geographical area. Rather, it represents a decisive moment in the evolution of India’s environmental constitutionalism. By grounding ecological protection firmly within constitutional principles, the court has reinforced the idea that environmental preservation is inseparable from fundamental rights, governance obligations, and democratic accountability.

Environmental Protection as a Constitutional Mandate

Constitutional Foundations of Environmental Jurisprudence

Indian environmental law has long drawn strength from constitutional provisions rather than relying solely on statutory enactments. Article 48A of the Constitution, introduced through the Forty-Second Amendment, imposes a duty on the State to protect and improve the environment and to safeguard forests and wildlife. Complementing this, Article 51A(g) casts a fundamental duty upon citizens to protect and improve the natural environment, including forests, lakes, rivers, and wildlife.

Beyond these explicit provisions, the judiciary has played a transformative role by interpreting Article 21—the right to life and personal liberty—in an expansive manner. Through a series of landmark judgments, the Supreme Court has consistently held that the right to life includes the right to live in a clean, healthy, and pollution-free environment. This interpretative approach has elevated environmental protection from a policy objective to an enforceable constitutional guarantee.

Constitutionalization of Environmental Governance in the Aravalli Judgment

Building upon this jurisprudential foundation, the Aravalli judgment reiterates that environmental protection is not a matter of administrative discretion or political expediency. The court emphasized that ecological degradation directly undermines the right to life, health, and human dignity. By linking environmental harm to constitutional injury, the judgment reinforces the principle that environmental governance is anchored in constitutional values and obligations.

This approach marks a shift from viewing environmental regulation as merely statutory compliance toward recognizing it as a constitutional imperative. The ruling thus strengthens the normative force of environmental protection within India’s constitutional framework.

Recognition of Ecological Limits and the Principle of Intergenerational Equity

Acknowledging Ecological Thresholds

One of the most significant contributions of the Aravalli judgment lies in its explicit recognition of ecological limits. The court acknowledged that ecosystems possess finite regenerative capacities and that unchecked mining, construction, and development in ecologically sensitive zones cause irreversible and cumulative damage. This acknowledgment reflects a departure from development-centric decision-making that prioritizes short-term economic gains over long-term ecological stability.

By emphasizing scientific assessment and ecological sensitivity, the judgment signals a move toward sustainability-based governance. It recognizes that environmental harm is not always immediately visible but often manifests over time through groundwater depletion, loss of biodiversity, and climate vulnerability.

Intergenerational Equity as a Constitutional Value

Closely connected to the recognition of ecological limits is the court’s reaffirmation of the principle of intergenerational equity. This principle rests on the idea that present generations hold natural resources in trust for future generations and are duty-bound to use them responsibly. The Aravalli judgment underscores that developmental activities must not compromise the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.

By restraining environmentally destructive activities in the Aravalli region, the court affirmed that economic interests cannot override long-term ecological survival. In doing so, it aligned domestic constitutional interpretation with global environmental norms and sustainable development principles.

Strengthening the Public Trust Doctrine

The State as Trustee of Natural Resources

Another critical dimension of the Aravalli judgment is its reliance on the public trust doctrine. Under this doctrine, natural resources such as forests, mountains, rivers, and wetlands are not owned by the State in a proprietary sense. Instead, they are held in trust for the benefit of the public. The State acts as a trustee and is obligated to protect these resources from exploitation and degradation.

The court’s application of this doctrine in the Aravalli case reinforces the idea that the government cannot permit commercial or private activities that fundamentally alter or destroy natural resources. Any such action would constitute a breach of trust and invite judicial scrutiny.

Enhancing Accountability and Citizen Participation

By invoking the public trust doctrine, the judgment strengthens accountability in environmental governance. It places a clear responsibility on public authorities to justify their actions and decisions affecting ecological assets. Moreover, it empowers citizens and civil society organizations to challenge governmental policies and permissions that threaten environmental integrity.

This aspect of the ruling deepens democratic engagement in environmental protection and reinforces transparency in decision-making processes.

Judicial Activism and Environmental Governance

Filling Governance Gaps Through Judicial Intervention

The Aravalli judgment exemplifies the proactive role played by the Indian judiciary in environmental governance. In many instances, courts have intervened to address regulatory failures, weak enforcement, and institutional inertia. While judicial activism in environmental matters has sometimes been criticized as encroaching upon executive functions, the Aravalli ruling demonstrates that such intervention becomes necessary when environmental degradation poses a direct threat to fundamental rights.

The judgment reflects a careful balance between constitutional oversight and administrative responsibility, emphasizing that judicial intervention is warranted where governance mechanisms fail to protect ecological interests.

Emphasis on Preventive and Precautionary Approaches

Significantly, the ruling underscores the importance of strict compliance with environmental clearance procedures, scientific assessments, and sustainable planning norms. It reinforces the preventive and precautionary principles of environmental law, shifting the focus from post-damage remediation to anticipatory protection.

This approach represents a mature evolution in Indian environmental jurisprudence, recognizing that prevention is more effective and just than attempting to repair irreversible environmental harm.

Reinforcing the Concept of Green Constitutionalism

Environmental Values at the Constitutional Core

Green constitutionalism refers to the integration of environmental protection into constitutional interpretation, governance structures, and rights discourse. The Aravalli judgment stands as a clear manifestation of this concept in practice. By embedding environmental considerations within fundamental rights and constitutional duties, the court elevated ecological protection to the highest normative level.

This integration ensures that environmental concerns are not subordinated to economic development but are treated as essential to human welfare and constitutional governance.

Sustainable Development as a Guiding Principle

Rather than rejecting development altogether, the judgment reinforces sustainable development as the guiding constitutional principle. It recognizes that economic growth and environmental protection are not mutually exclusive but must be harmonized. By insisting on ecological balance and long-term sustainability, the ruling strengthens India’s position as a global leader in constitutional environmentalism.

Conclusion: A Turning Point in India’s Environmental Jurisprudence

The Aravalli judgment marks a decisive turning point in India’s environmental jurisprudence. It reaffirms the constitutional mandate to protect nature, strengthens the application of foundational environmental principles, and underscores the judiciary’s role in maintaining ecological balance. More importantly, it reflects a shift toward a mature and responsible model of environmental governance that acknowledges the interdependence of constitutional values, ecological sustainability, and human rights.

As environmental challenges intensify due to climate change, urbanization, and resource depletion, the principles articulated in the Aravalli judgment will continue to guide legal and policy decisions. By embedding environmental protection within India’s constitutional identity, the ruling ensures that ecological preservation remains central to the nation’s democratic and developmental aspirations.

Unlock the Potential of Legal Expertise with LegalMantra.net - Your Trusted Legal Consultancy Partner”

Disclaimer: Every effort has been made to avoid errors or omissions in this material in spite of this, errors may creep in. Any mistake, error or discrepancy noted may be brought to our notice which shall be taken care of in the next edition In no event the author shall be liable for any direct indirect, special or incidental damage resulting from or arising out of or in connection with the use of this information Many sources have been considered including Newspapers, Journals, Bare Acts, Case Materials , Charted Secretary, Research Papers etc

LegalMantra.net team

Prerna Yadav