View News

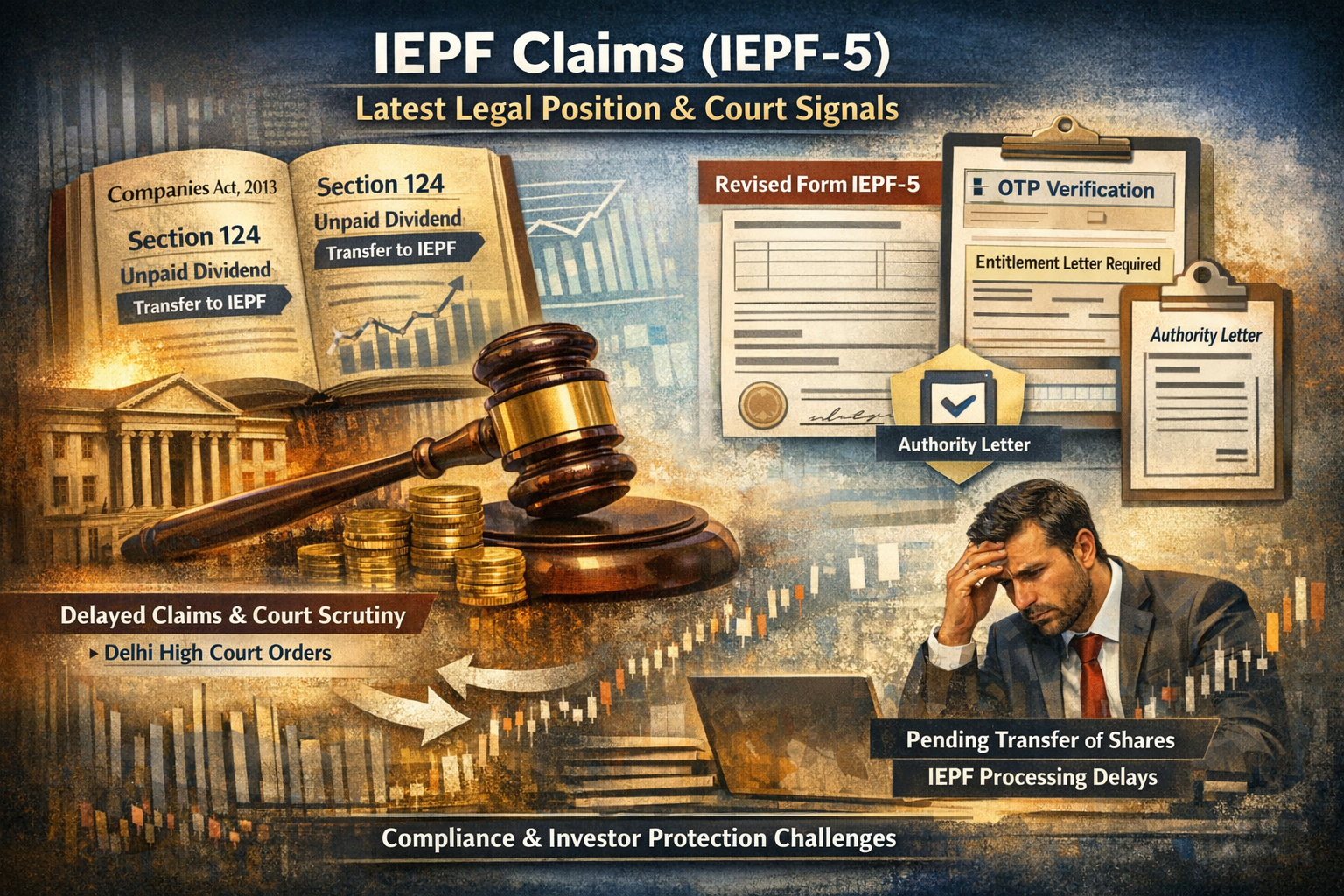

IEPF Claims (Form IEPF?5): Latest Legal Position, Procedural Changes and Emerging Judicial Trends

IEPF Claims (Form IEPF-5): Latest Legal Position, Procedural Changes and Emerging Judicial Trends

Introduction

The Investor Education and Protection Fund framework under the Companies Act, 2013 has evolved far beyond a routine compliance exercise handled mechanically by finance teams or registrars. Continuous amendments to procedural rules, the substitution of Form IEPF?5, and increasing intervention by constitutional courts have collectively transformed IEPF compliance into a rights?centric and governance?sensitive legal process. Today, IEPF matters lie at the confluence of investor protection, corporate compliance, and administrative accountability.

From an investor’s perspective, the emphasis is on timely and effective restitution of dividends and shares that have been transferred to the Fund. For companies, particularly listed entities, the focus has shifted to accuracy in statutory transfers, structured internal verification mechanisms, and prompt cooperation with the Investor Education and Protection Fund Authority. This article analyses the current legal position governing IEPF claims, explains the practical implications of the substituted Form IEPF?5, and examines recent judicial trends that are reshaping the manner in which IEPF claims are processed and enforced.

1. Statutory Framework Governing IEPF under the Companies Act, 2013

1.1 Section 124: Unpaid Dividend and Transfer to IEPF

Section 124 of the Companies Act, 2013 governs the treatment of unpaid and unclaimed dividends and prescribes the circumstances under which such amounts, along with the underlying shares, are required to be transferred to the Investor Education and Protection Fund. The statutory scheme under this provision operates in a phased manner.

In the first stage, any dividend declared by a company that remains unpaid or unclaimed for a period of thirty days from the date of declaration is required to be transferred to a designated account known as the Unpaid Dividend Account. This account serves as an intermediate holding mechanism and ensures segregation of unclaimed amounts from the company’s general funds.

In the second stage, where the dividend continues to remain unpaid or unclaimed for a continuous period of seven years, the amount standing to the credit of the Unpaid Dividend Account is mandatorily required to be transferred to the Investor Education and Protection Fund. This transfer is statutory in nature and leaves no discretion with the company once the conditions are satisfied.

A more significant compliance obligation arises in relation to shares on which dividends have not been paid or claimed for seven consecutive years. In such cases, Section 124 mandates the transfer of the underlying shares themselves to the IEPF Authority. This requirement has far?reaching consequences, as it involves extinguishment of the shareholder’s name from the company’s register and transmission of the shares to the Authority’s demat account.

A critical clarification embedded in the statutory framework is that if the dividend is paid or claimed for even a single year within the seven?year period, the shares cannot be transferred to the IEPF. This nuance is of substantial practical importance and continues to be a frequent source of non?compliance, often resulting in wrongful transfer of shares due to inadequate historical dividend tracking by companies.

1.2 Section 125: Constitution of IEPF and Statutory Right to Refund

Section 125 of the Companies Act, 2013 formally establishes the Investor Education and Protection Fund and specifies the categories of amounts that are required to be credited to it. These include amounts transferred under Section 124, matured deposits, matured debentures, application money due for refund, as well as interest income and other incidental accruals associated with the Fund.

The most consequential aspect of Section 125 is its explicit recognition of the right of a claimant to seek refund of shares, dividends, or other amounts that have been transferred to the IEPF. The statutory language makes it clear that transfer to the Fund does not amount to forfeiture. Instead, the IEPF operates as a custodial mechanism, preserving investor entitlements subject to compliance with the prescribed procedural framework.

2. Procedural Framework under the IEPF Authority Rules, 2016

The Investor Education and Protection Fund Authority (Accounting, Audit, Transfer and Refund) Rules, 2016 provide the procedural architecture for operationalising Sections 124 and 125 of the Act. These rules define the manner in which transfers are to be made to the Fund and, more importantly, the process through which claimants can seek refunds.

2.1 Rule 7: Refund Mechanism through Form IEPF-5

Rule 7 constitutes the core of the refund mechanism under the IEPF framework. It requires an eligible claimant to file Form IEPF-5 electronically with the IEPF Authority. Upon filing, the form is transmitted through the electronic system to the Nodal Officer of the concerned company for verification of the claim.

The company, acting through its designated Nodal Officer, is required to examine the claim, verify the underlying records, and submit an online verification report to the IEPF Authority within the prescribed timeline. Only upon receipt of a satisfactory verification report does the Authority proceed to process the claim and release the refund or initiate the transmission of shares and dividends to the claimant’s demat and bank accounts.

In practice, delays or deficiencies at the company verification stage have emerged as the most significant bottleneck in the IEPF refund process. This stage has consequently become the focal point of both regulatory scrutiny and judicial intervention.

3. Substituted Form IEPF-5 and Its Practical Implications

The Ministry of Corporate Affairs has notified amendments with effect from 6 October 2025, substituting the existing Form IEPF-5 with a revised form. While the substantive right of investors to claim refunds remains unchanged, the revised form introduces a heightened level of procedural rigor and front?loads documentation requirements at the filing stage.

3.1 Key Operational Changes in the Revised Form

One of the most notable changes introduced through the substituted Form IEPF?5 is the mandatory requirement to upload an entitlement letter issued by the concerned company or bank. This requirement aims to reduce ambiguity in entitlement determination and ensure that claims are filed only after preliminary confirmation of entitlement, though it also increases the preparatory burden on claimants.

The revised form also formalises the authorised representative workflow. Where a claim is filed through an authorised representative, the form now requires disclosure of the representative’s details along with upload of a duly executed authority letter. This change is particularly relevant in cases involving legal heirs, senior citizens, and non-resident investors who commonly rely on professional assistance.

Additionally, the introduction of OTP based validation for both mobile number and email address reflects a broader push towards strengthened digital authentication. This aligns IEPF filings with the wider MCA e?governance ecosystem and reduces the scope for impersonation or defective filings.

3.2 Practical Consequences for Claimants and Companies

The substituted Form IEPF-5 effectively shifts the IEPF claim process from being document?intensive after filing to being document ready at the time of filing itself. Claims that are incomplete or casually prepared are now more likely to result in rejection, resubmission requirements, or prolonged verification cycles, thereby increasing timelines and litigation risk.

4. Judicial Trends and Increasing Court Intervention

High Courts across jurisdictions have shown a growing willingness to exercise writ jurisdiction in IEPF matters. The consistent judicial theme emerging from these cases is that procedural safeguards must not be permitted to defeat substantive investor rights.

4.1 Approval without Execution

In Kusum Mohan v. IEPF Authority, decided by the Delhi High Court on 14 May 2024, the petitioner demonstrated that although the Form IEPF-5 had been approved by the Authority, the actual transfer of shares and dividends had not been executed. The case brought into sharp focus the administrative inertia that often follows approval of claims.

The Court’s intervention in such matters signals that once a claim has been accepted on merits, prolonged execution delays are impermissible and can invite judicial correction.

4.2 Delays in Processing of Claims

In Gagan Deep Mehta v. IEPF Authority, decided by the Delhi High Court on 28 May 2025, the petitioner sought directions for expeditious processing of an IEPF?5 SRN relating to transmission of shares and dividends to a demat account. The case underscores that even in the absence of rigid statutory timelines, unexplained or excessive delays can amount to arbitrariness and justify invocation of writ jurisdiction under Article 226 of the Constitution.

4.3 Broader Judicial Message

Judicial decisions in IEPF matters do not seek to dilute statutory procedures. Instead, courts are reinforcing the principle that refunds under Section 125 are legal rights rather than discretionary concessions, that procedural requirements must remain proportionate to verification objectives, and that administrative inefficiency cannot be used as a justification for indefinite delay.

5. Compliance Implications for Companies

The evolving IEPF jurisprudence makes it clear that compliance can no longer be treated as a peripheral or clerical function. Companies are expected to establish structured internal mechanisms for handling IEPF verification, ensure effective coordination between secretarial, finance, and registrar teams, and maintain accurate historical dividend records to prevent wrongful transfers.

The role of the Nodal Officer has become particularly sensitive, as delays or lapses at this stage are now increasingly subjected to judicial scrutiny. Court monitored matters and long pending claims require priority handling to mitigate legal exposure and reputational risk.

6. Practical Considerations for Investors and Claimants

For investors, particularly under the revised Form IEPF-5 regime, meticulous preparation has become essential. The success and timeliness of an IEPF claim now depend largely on the accuracy and completeness of documentation submitted at the filing stage. Claimants must ensure that their demat account details, Permanent Account Number (PAN), Aadhaar particulars, and Know Your Customer (KYC) records are fully aligned across all relevant databases, including those maintained by depositories and intermediaries. Even minor discrepancies in name, date of birth, or address can lead to verification delays or rejection of the claim.

Obtaining the entitlement letter from the concerned company or bank in advance has become a critical preparatory step. Since the revised Form IEPF-5 mandates uploading of this document, claimants should factor in the time required for correspondence with the company or its registrar and transfer agent. Early procurement of the entitlement letter not only expedites filing but also reduces the likelihood of objections during the verification stage.

Claims should be filed with complete and legible supporting documents at the first instance, including succession documents in case of legal heirs and properly executed authority letters where authorised representatives are involved. Incomplete filings often result in resubmission cycles that significantly prolong the refund process.

After filing, investors should actively monitor the service request number generated upon submission of Form IEPF-5 and maintain written follow-ups with both the company’s Nodal Officer and the IEPF Authority wherever necessary. Passive reliance on the electronic system without follow-up frequently leads to stagnation of claims.

Where delays become excessive, unexplained, or disproportionate to the nature of verification required, investors should be aware that judicial remedies are increasingly available. Recent High Court decisions demonstrate that writ jurisdiction may be invoked where administrative inaction frustrates the statutory right to refund recognised under Section 125 of the Companies Act, 2013.

"Unlock the Potential of Legal Expertise with LegalMantra.net - Your Trusted Legal Consultancy Partner”

Disclaimer: Every effort has been made to avoid errors or omissions in this material in spite of this, errors may creep in. Any mistake, error or discrepancy noted may be brought to our notice which shall be taken care of in the next edition In no event the author shall be liable for any direct indirect, special or incidental damage resulting from or arising out of or in connection with the use of this information Many sources have been considered including Newspapers, Journals, Bare Acts, Case Materials , Charted Secretary, Research Papers etc

LegalMantra.net team

Mayank Garg