View News

A Jurisprudential Reappraisal of Maintenance Rights under Hindu Law An Analysis of Kanchana Rai Geeta Sharma

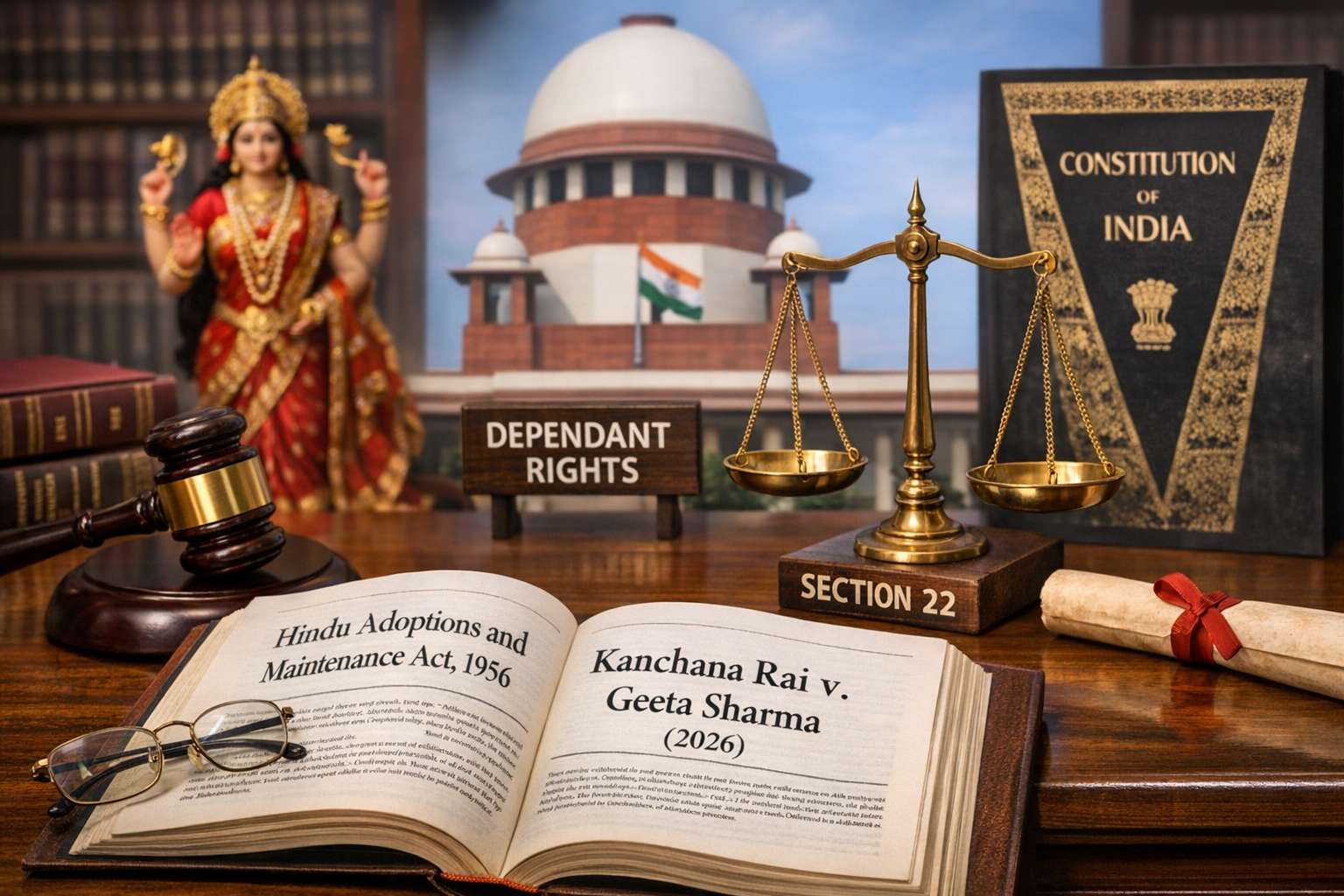

A Jurisprudential Reappraisal of Maintenance Rights under Hindu Law:

An Analysis of Kanchana Rai v. Geeta Sharma

Introduction

The decision of the Supreme Court in Kanchana Rai & Anr. v. Geeta Sharma & Ors. (2026 INSC 54) constitutes a significant doctrinal development in the interpretation of maintenance rights under the Hindu Adoptions and Maintenance Act, 1956 (HAMA). Moving beyond a narrow textual reading of statutory provisions, the Court adopted a purposive and rights-oriented interpretive approach to expand the understanding of the term “dependant” under the Act. In doing so, it reaffirmed the transformative constitutional ethos that increasingly informs the interpretation of personal laws in India.

The central issue before the Court was deceptively simple yet legally profound: whether a woman who becomes a widow after the death of her father-in-law can claim maintenance from his estate under Section 22 of HAMA. The Supreme Court answered this question in the affirmative, thereby strengthening the economic safeguards available to widowed daughters-in-law and reinforcing the welfare character of maintenance jurisprudence.

Factual Matrix and Procedural Background

The dispute arose from the estate of Dr. Mahendra Prasad, who died intestate in 2021, leaving behind three sons. One of the sons had predeceased him. Subsequently, in 2023, another son, Ranjit Sharma, passed away, leaving behind his widow, Geeta Sharma. Prior to his death, Dr. Prasad had executed a will primarily in favour of his surviving heirs.

Following her husband’s demise, Geeta Sharma sought maintenance from her deceased father-in-law’s estate under Sections 21 and 22 of HAMA, asserting that she qualified as a “dependant.” The Family Court rejected her claim on the ground that she was not a widow at the time of her father-in-law’s death and therefore did not satisfy the statutory requirement.

On appeal, the Delhi High Court reversed this decision, holding that such a restrictive and temporal interpretation would defeat the object of the statute. The matter was then carried to the Supreme Court, where the issue crystallised into a question of statutory construction with wide social implications.

Statutory Framework: Concept of “Dependant” and the Right to Maintenance

The controversy centred around Sections 21 and 22 of HAMA.

Section 21 defines “dependants” and expressly includes “the widow of a son of the deceased.” Section 22 creates the enforceable obligation, stipulating that the heirs of a deceased Hindu are bound to maintain the dependants out of the estate inherited by them.

The interpretive tension arose from whether the expression “widow of a son” must be temporally fixed at the moment of the propositus’ death, or whether the status of widowhood could arise subsequently and still attract the statutory protection.

The Court analysed the structural relationship between Sections 19 and 22, clarifying their distinct spheres of operation. This distinction may be illustrated as follows:

| Provision | Nature of Obligation | Operative Stage | Source of Liability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Section 19 | Personal obligation of father-in-law | During his lifetime | Individual responsibility |

| Section 22 | Obligation of heirs to maintain dependants | After death of propositus | Charge on inherited estate |

Through this structural clarification, the Court emphasised that Section 22 does not impose a personal obligation on the deceased but creates a statutory charge on the estate inherited by the heirs. Therefore, the widow’s status at the time of the father-in-law’s death is not determinative.

Judicial Reasoning and Interpretive Methodology

Rejection of Restrictive Literalism

The Supreme Court categorically rejected a narrow literal interpretation that would freeze the status of “widow of a son” at the time of the father-in-law’s death. It noted that Section 21(vii) contains no temporal qualifier limiting its application to widows existing at that precise moment.

To read such a restriction into the provision, the Court held, would amount to judicial legislation. The absence of express statutory limitation was interpreted as deliberate legislative design. Courts, therefore, must refrain from importing artificial constraints not contemplated by Parliament.

This reasoning reflects fidelity to settled principles of statutory interpretation: where the language is plain and unqualified, courts cannot read into it words that are not present.

Purposive and Welfare-Oriented Construction

The Court further observed that HAMA is a beneficial social welfare legislation intended to prevent destitution among vulnerable family members. Maintenance statutes, by their very nature, must be interpreted liberally to advance their remedial objective.

Relying on earlier precedents such as Vimala v. Veeraswamy and Kirtikant D. Vadodaria v. State of Gujarat, the Court reiterated that maintenance provisions must be construed in favour of the claimant where ambiguity exists. A rigid temporal interpretation, the Court reasoned, would defeat the protective object of the Act and undermine its social justice orientation.

The Court thus located its reasoning within the broader doctrinal framework that welfare statutes deserve liberal interpretation, especially when they concern gender justice.

Harmonisation of Sections 19 and 22

A notable contribution of the judgment lies in its doctrinal harmonisation of Sections 19 and 22. Section 19 provides for maintenance of a widowed daughter-in-law during the lifetime of the father-in-law, subject to certain conditions. Section 22, on the other hand, operates independently and posthumously.

The Court clarified that the two provisions are not mutually dependent. Section 22 creates an obligation attached to the estate and not to the individual. Consequently, the timing of widowhood is irrelevant so long as, at the time the claim is made, the claimant satisfies the description of a “widow of a son” and the estate remains with the heirs.

This interpretation prevents a lacuna where a daughter-in-law could be left remediless merely because widowhood occurred after the father-in-law’s demise.

Constitutional Infusion: Articles 14 and 21

The judgment is also significant for its explicit constitutional underpinnings. The Court held that denying maintenance solely on the basis of the timing of widowhood would amount to an arbitrary classification lacking intelligible differentia, thereby offending Article 14 of the Constitution.

Furthermore, maintenance is intimately connected with the right to live with dignity under Article 21. Economic security for a destitute widow is not merely a matter of statutory entitlement but a facet of substantive equality and human dignity.

In this sense, the decision reflects the broader trend of constitutionalising personal laws, evident in transformative rulings such as Navtej Singh Johar v. Union of India and Joseph Shine v. Union of India, where the Court harmonised traditional legal doctrines with constitutional morality.

Doctrinal and Jurisprudential Significance

The ruling advances three major doctrinal themes.

First, it strengthens the proprietary and economic rights of widows by eliminating technical barriers that historically disadvantaged them. By recognising the estate-based nature of the obligation, the Court ensures continuity of financial protection.

Second, it reinforces the doctrine of beneficial interpretation, affirming that social welfare statutes must be construed liberally to fulfil their remedial purpose.

Third, it deepens the constitutionalisation of personal law by embedding equality and dignity principles into statutory interpretation. The judgment thus exemplifies the synthesis between statutory construction and constitutional morality.

Critical Reflections

Despite its progressive orientation, the judgment leaves certain issues open for future adjudication. The Act does not provide a precise formula for quantifying maintenance, leaving considerable discretion to courts. This may produce inconsistencies in awards across jurisdictions.

Additionally, the decision may be viewed as limiting testamentary autonomy where property is disposed of through a will. Since Section 22 attaches liability to the inherited estate, even testamentary transfers may be subject to maintenance claims.

Finally, disparities persist across different personal law regimes. The protective framework under HAMA does not automatically extend to women governed by other religious laws, thereby raising broader concerns of uniformity and equality.

Nevertheless, these concerns do not dilute the normative force of the judgment, which prioritises substantive justice over technical formalism.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court’s decision in Kanchana Rai v. Geeta Sharma stands as a doctrinally sophisticated and socially responsive exposition of maintenance law under the Hindu Adoptions and Maintenance Act, 1956. By affirming that a daughter-in-law who becomes a widow after the father-in-law’s death remains a “dependant” under Section 22, the Court has clarified a long-standing ambiguity and strengthened the protective architecture of Hindu personal law.

More importantly, the judgment reflects the evolving judicial commitment to aligning personal laws with constitutional values of equality, dignity, and social justice. In doing so, it underscores the judiciary’s enduring role as a guardian of vulnerable familial relationships within a transforming constitutional order.

"Unlock the Potential of Legal Expertise with LegalMantra.net - Your Trusted Legal Consultancy Partner”

Disclaimer: Every effort has been made to avoid errors or omissions in this material in spite of this, errors may creep in. Any mistake, error or discrepancy noted may be brought to our notice which shall be taken care of in the next edition In no event the author shall be liable for any direct indirect, special or incidental damage resulting from or arising out of or in connection with the use of this information Many sources have been considered including Newspapers, Journals, Bare Acts, Case Materials , Charted Secretary, Research Papers etc

Prerna Yadav

LegalMantra.net team