View News

Religious-Fundamentalism

Religious Fundamentalism

~Sura Anjana Srimayi

INTRODUCTION

Amidst a more globalized and interconnected world, the resurgence and ongoing power of religious fundamentalism are a paradoxical phenomenon. While modernity tends to celebrate progress, pluralism, and secular rule, fundamentalist movements tend to campaign for a return to what they believe are original, pure religious teachings, usually seeing present-day societal changes as moral degeneration. This allegiance to a ultimate truth, felt to be Godly-commanded and unchangeable, may create strong social solidarity among its supporters but may also give rise to intolerance, discrimination, and, in the most extreme situations, brutality against those who are "outsiders" or "apostates." Religious fundamentalism is not an abstract field of study; it is vital to understanding modern-day conflicts, political realignments, and the constant battles for human rights and secular authority in some regions of the globe.

Deconstructing Religious Fundamentalism: Origins and Characteristics

The term "fundamentalism" originated in the late 19th and early 20th centuries within American Protestantism, describing a movement that sought to defend the "fundamentals" of Christian belief against the perceived threats of modernism, scientific advancements (like Darwinism), and liberal theological interpretations. Over time, the term broadened to encompass similar movements across various religions, including Islam, Hinduism, Judaism, Sikhism, and Buddhism, which exhibit analogous characteristics.

- Literal Interpretation of Sacred Texts: Fundamentalism is characterized by its assumption that sacred writings (e.g., the Bible, Quran, Vedas) represent the inerrant and literal word of God and are a final and fixed guide for all aspects of life. This tends to mean that allegorical or contextual interpretations are discarded.

- Rejection of Modernity and Secularism: Fundamentalists tend to perceive modern values, including secular government, pluralism, individualism, and scientific discoveries, as corrosive to their religion and social order. They can support a society ruled by their definition of divine law, in some instances resulting in the calls for theocracy.

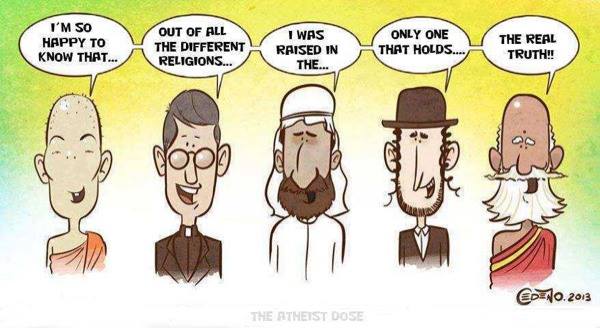

- Exclusivism and Dualism: Fundamentalist thinking is frequently characterized by a strong "us vs. them" sentiment, separating the righteous (believers) from the unrighteous (non-believers or dissidents with other interpretations). This can breed intolerance of other religions or dissident viewpoints within their own faith.

- Aspiration for Societal Change: Most fundamentalist movements strive to reorganize society and public life based on their theological teachings, spreading their influence beyond personal piety to legal, educational, and political contexts. This may involve espousing law derived from religious scriptures, enforcing moral purity, and regulating public speech.

- Selective Traditionalism: Whereas fundamentalists may call for a "return" to "traditional" values, this return is frequently selective, reading history and tradition in a manner that validates their agenda at the time but not necessarily sticking to a historically sensitive, well-rounded past.

- Authoritarian Leadership: Fundamentalist movements tend to center around charismatic leaders who play the role of interpreters of doctrine and have considerable authority over their members.

- Militancy (in extreme forms): Although not all fundamentalists are violent, the most extreme groups might use aggression or violence in order to protect their religious identity, gain political objectives, or impose their conception of divine law, often perceiving such actions as divinely ordained. It is important to differentiate between religious fundamentalism, an ideological position, and religious extremism or fanaticism, which refers to being prepared to employ radical means, including violence, to attain religious ends.

Legal Implications and Challenges in Secular Democracies

Rising religious fundamentalism poses serious challenges to the law of secular democracies, which is based on the precepts of equality, individual rights, and separation of church and state. Trying to balance the constitutional promise of religious freedom with the necessity to ensure public order, safeguard minority rights, and preserve human dignity is an ever-enduring legal tightrope walk.

A. Religious Freedom and Public Order, Morality, and Health:

The majority of democratic constitutions, including the Indian one, ensure freedom of conscience and the right to profess, practice, and propagate religion (e.g., Articles 25-28 of the Indian Constitution). These rights are usually not absolute. They are generally subject to "reasonable restrictions" in respect of public order, morality, and health, and to other basic rights.

- Public Order: This is the most common restriction. Religious gatherings, processions, or practices likely to lead to violence in communities or that directly cause harm to public peace can be restricted or outlawed by the state. Courts usually balance the right to religious assembly against the state's responsibility to keep the peace. For example, in India, police regulate religious procession routes or timings to avoid clashes.

- Morality: This limitation tends to result in intricately legalised argumentation. Absolute readings of morality may conflict with changing social mores and personal rights, especially relating to gender equity, gay rights, and autonomy. Matters relating to the entry of women into religious institutions (such as the Sabarimala Temple case in India) or discriminatory religious practice tend to require the courts to interpret "morality" by reference to principles of constitutional law such as equality and non-discrimination.

- Health: Religious practices constituting a risk to public health (e.g., certain pandemic rituals, or injurious practices) can be made legally unfeasible.

B. Hate Speech and Incitement to Violence:

Religious fundamentalism, especially its more virulent manifestations, can create a climate in which hate speech becomes prevalent, encouraging enmity, hatred, or ill-will against an offenden't religious group. The great majority of legal systems contain provisions criminalizing such speech, as they are seen as liable to upset social cohesion and provoke violence.

In India, sections 153A and 295A of the Indian Penal Code (IPC) are essential in this context. Section 153A criminalizes inciting enmity between groups based on religion, race, place of birth, residence, language, etc. Section 295A deals with deliberate and malicious intention to outrage religious feelings. Although these enactments seek to prevent religious fundamentalists' efforts at promoting discord, their enforcement usually attracts criticism for possibly crossing the limits of freedom of speech or getting used to suppress valid criticism of religious rituals. The problem for courts is to distinguish between authentic hate speech aimed at promoting violence and legitimate statements of religious belief, no matter how offensive, or bona fide criticism.

C. Anti-Conversion Laws:

A controversial area of law in India closely related to issues of religious fundamentalism are the state-level "Freedom of Religion Acts" or anti-conversion laws. A number of Indian states (Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat, Himachal Pradesh) have promulgated such laws, mainly in order to discourage religious conversions by "force, fraud, or inducement." While supporters claim these laws safeguard vulnerable people from forced conversions and preserve communal harmony, opponents believe they usually violate a person's right to adopt a religion of their choice, particularly when conversion for the sake of marriage becomes the target, and are even used to harass religious minorities. The Indian Supreme Court has generally maintained the right to spread one's religion but has also endorsed the ability of the state to stop forced conversions. The legal conflicts over these laws resonate with the conflict between collective societal concerns and individual religious freedom.

D. Human Rights and Gender Equality:

Religious fundamentalism tends to conflict with international human rights norms, especially with regard to gender equality, freedom of expression, and minority rights. Numerous faithful fundamentalist interpretations themselves promote traditional, usually patriarchal, gender distinctions that can severely limit women's autonomy, education, work opportunities, and public life. Legislation premised on such interpretations, prevalent in certain theocratic or fundamentalist-influenced governments (e.g., the Taliban regime in Afghanistan, or elements of legal systems in Iran and Saudi Arabia based on strict Islamic jurisprudence), can generate institutionalized discrimination against women and human rights violations.

From a legal point of view, democratic nations struggle with how to step in with respect to practices that, although religiously justified, contravene general principles of universal human rights. This is usually through judicial review of personal laws (which cover issues of marriage, divorce, and inheritance on the basis of religious traditions) to guarantee adherence to constitutional provisions of equality and non-discrimination.

E. Religious Fundamentalism and Terrorism:

In its most virulent form, religious fundamentalism can become religiously inspired terrorism. Organizations such as Al-Qaeda, ISIS, and Boko Haram illustrate how perverted religious ideologies can serve as the basis for condoning mass violence, random killings, and plots to overthrow secular states. International law and national anti-terrorism laws are created to resist such menaces. Such legal responses target:

- Criminalization of Terrorist Acts: Definition and prosecution of acts of terrorism, terrorism financing, and terrorism incitement.

- International Cooperation: Extradition agreements, intelligence sharing, and mutual legal assistance to counter cross-border religious extremism.

- Deradicalization Programs: While largely social and psychological, legal frameworks can assist in programs of disengagement from extremist ideology.

- Still, legal strategies also need to be careful not to conflate the beliefs and practices of a whole religion with those of a terrorist fringe, so that it does not inadvertently punish legitimate religious practice or create discrimination.

F. Challenges to Secularism

Religious fundamentalism threatens the very principle of secularism, which in the Indian context means not state-religion separation, but equal respect for all religions ("Sarva Dharma Sambhava") and neutrality of the state with regard to religious matters. Fundamentalist groups tend to undermine this neutrality by seeking patronage by the state for their particular religion, applying religious precepts to public policy, or promoting the application of religious law over civil law. The judicial system, and in particular the courts, become the ultimate court of appeal in upholding the secular character of the country against such intrusions.

Regulatory Framework and Future Scenario in India

India's constitutional pledge to secularism and religious diversity render it an essential case study of the interaction between religious fundamentalism and law. Though the Indian Constitution provides sweeping religious liberties, it also authorizes the state to manage religious matters in the cause of social reform and public order.

The Supreme Court of India has reaffirmed secularism as an "basic feature" of the Constitution, i.e., unamendable even through constitutional amendment. The doctrine is a crucial legal shield against moves by fundamentalists to turn India into a confessional state. Path-breaking decisions regarding religious practices, personal laws, and minority rights keep refashioning the outlines of religious freedom within a plural polity.

The legal wars, however, continue. Identity politics commonly witnesses religious fundamentalist discourses acquiring ascendance and mobilizing legislative reform that could permit majority religious views or curtail minority practices. The task for Indian law is to regularly interpret constitutional provisions in a way that safeguards the rights of all citizens, avoids discrimination, and maintains the ethos of pluralism and tolerance despite pressure from fundamentalist forces.

Coming legal remedies will include:

- Better Definitions: Creating better legal definitions for terms such as "hate speech" and "coercion" in conversion, to avoid ambiguity and abuse.

- Judicial Activism: Ongoing supervision by the judiciary to see that actions by the legislature or the executive do not violate fundamental rights in the name of public order or religious protection.

- Fostering Constitutional Literacy: Raising popular understanding of constitutional rights and the parameters of religious freedom, to counter misrepresentations by fundamentalist ideologies.

- International Norms: Drawing increasingly on international human rights conventions and principles in developing domestic legislation on religious practice, particularly in relation to women's rights and minority rights.

CONCLUSION

Religious fundamentalism, with its unshakeable adherence to perceived pure doctrines and frequently inflexible worldview, presents multifaceted socio-legal challenges for contemporary, pluralistic societies. Religious freedom is a standard of democratic government, yet it is not an unfettered liberty. The law, especially in secular nations such as India, repeatedly strives to define the limits of this freedom, never allowing the practice and spread of religion to infringe on public order, morality, health, or the basic rights of others.

The legal reactions to religious fundamentalism range from hate speech legislation and anti-conversion laws to staunch advocacy of constitutional secularism and human rights. Navigating this complicated terrain takes judicial insight, legislative prudence, and a social engagement with dialogue and tolerance. In the end, protecting the values of equality, justice, and human dignity in the context of fundamentalist challenges is an ongoing undertaking that is vital to creating inclusive and harmonious societies in the 21st century. The continuous development of legal systems worldwide and in India is a manifestation of this ongoing and essential conflict to reconcile deeply ingrained convictions with the necessity of a just and equitable society.

"Unlock the Potential of Legal Expertise with LegalMantra.net - Your Trusted Legal Consultancy Partner”

Disclaimer: Every effort has been made to avoid errors or omissions in this material in spite of this, errors may creep in. Any mistake, error or discrepancy noted may be brought to our notice which shall be taken care of in the next edition In no event the author shall be liable for any direct indirect, special or incidental damage resulting from or arising out of or in connection with the use of this information Many sources have been considered including Newspapers, Journals, Bare Acts, Case Materials , Charted Secretary, Research Papers etc